Can a philosopher fully embrace religious dogma without compromising the core of philosophical inquiry? Or does the relentless pursuit of wisdom through reason, evidence, and questioning inevitably create friction with beliefs accepted on authority or faith? This longstanding debate has shaped Western thought for millennia. While some thinkers see philosophy and religion as complementary paths to truth, others view dogma as a barrier to genuine intellectual freedom. Below, we delve deeper into the key arguments, historical figures, and nuances on both sides.

The Nature of Philosophical Inquiry

Philosophy is fundamentally the love of wisdom pursued through critical examination, logical argumentation, and openness to revision. Socrates captured this ethos in his famous assertion that “the unexamined life is not worth living,” emphasizing relentless questioning of assumptions about ethics, knowledge, politics, and the divine.

This method often stands in tension with dogma...beliefs held as authoritative without requiring ongoing justification or evidence. Religious traditions, which frequently rely on revelation, sacred texts, prophetic authority, or communal faith, exemplify this for many critics. For instance, David Hume challenged the reliability of miracles and religious claims that defy natural laws, arguing that extraordinary claims demand extraordinary evidence.

The philosophical commitment to skepticism and falsifiability (echoed later by Karl Popper) means that no belief should be immune to scrutiny. When dogma demands acceptance on faith alone, it can appear to halt the inquiry process, turning philosophy into something closer to apologetics.

Perspectives of Compatibility

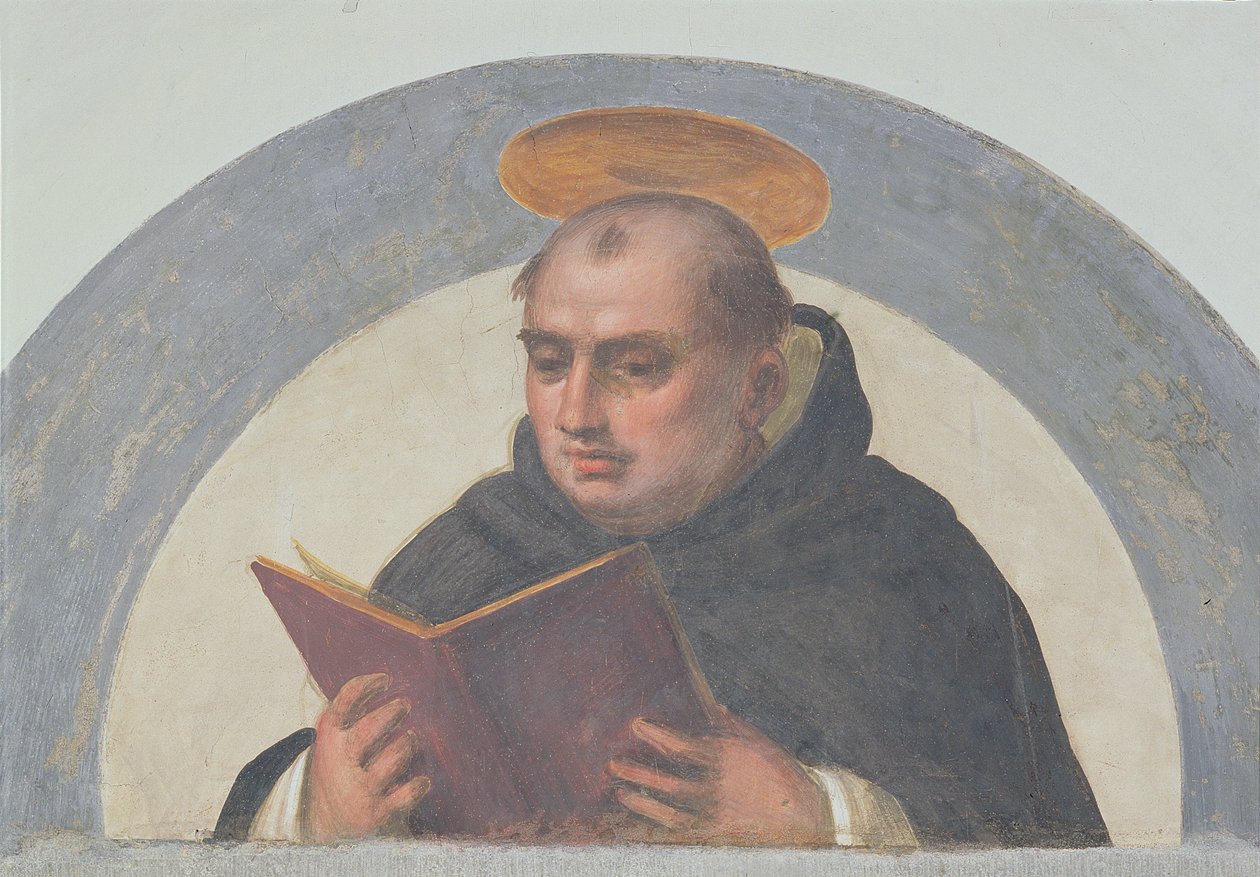

A significant tradition argues that faith and reason can coexist productively. Medieval thinker Thomas Aquinas famously synthesized Aristotelian philosophy with Christian theology, asserting that reason and revelation are both paths to truth from the same divine source. He maintained that faith and reason complement each other: reason can demonstrate certain truths about God (like existence via the Five Ways), while revelation provides truths beyond reason’s reach. One well-known formulation attributed to him is: “To one who has faith, no explanation is necessary. To one without faith, no explanation is possible.”

In the modern era, Baruch Spinoza developed a pantheistic system where God is identical with nature, derived purely through rational deduction rather than faith. Søren Kierkegaard, while embracing the “leap of faith” as essential for authentic religious existence, still engaged deeply with philosophical questions, viewing faith as addressing subjective, existential truths that objective reason cannot fully grasp.

Contemporary philosopher Alvin Plantinga’s Reformed Epistemology offers another bridge: belief in God can be “properly basic,” meaning it is rational without needing evidential support from arguments...just as belief in other minds or the external world is basic. This challenges the evidentialist demand for proof, suggesting religious belief can be epistemically warranted independently.

These views portray religion not as anti-philosophical but as addressing dimensions (moral, existential, metaphysical) that pure reason might leave incomplete.

Contrasting Historical Views

On the other side, prominent critics argue that religious dogma undermines philosophical autonomy. Bertrand Russell, in Why I Am Not a Christian, contended that traditional theology lacks evidential support and is rooted in fear: “Religion is based, I think, primarily and mainly upon fear. It is partly the terror of the unknown...” He concluded, “there is no reason to believe any of the dogmas of traditional theology and... no reason to wish that they were true.”

Friedrich Nietzsche’s proclamation “God is dead. God remains dead. And we have killed him” (from The Gay Science) reflects the cultural shift after the Enlightenment: the decline of belief in the Christian God as foundational to values, leading to a crisis of meaning and morality. Nietzsche saw this not as mere atheism but as an opportunity and challenge for humanity to create new values without reliance on dogmatic frameworks.

Yet history shows many religious philosophers (e.g., Augustine, Anselm, or modern analytic philosophers of religion) who produce rigorous work while holding dogmatic commitments, suggesting the tension is navigable for some.

Dogma in Broader Contexts

Dogma extends beyond religion to any unquestioned authority: political ideologies, cultural norms, scientific paradigms (as Thomas Kuhn described in The Structure of Scientific Revolutions), or even secular “certainties.” The philosophical disposition...skepticism, evidence-seeking, and willingness to revise acts as a universal safeguard.

In today’s world, echo chambers on social media or ideological polarization can mimic religious dogma in rigidity. Philosophy’s value lies in its insistence on examining all assumptions, religious or otherwise.

Continuing the Conversation

The interplay between philosophy and religious dogma remains profoundly open. Some traditions find harmony through synthesis; others highlight irreconcilable tensions that demand intellectual independence. The debate itself exemplifies philosophy’s vitality...questioning, refining, and never settling into finality.

What do you think? Does religious faith enhance or constrain philosophical depth? Share your thoughts in the comments!

Until next time, keep exploring the cosmos of ideas.